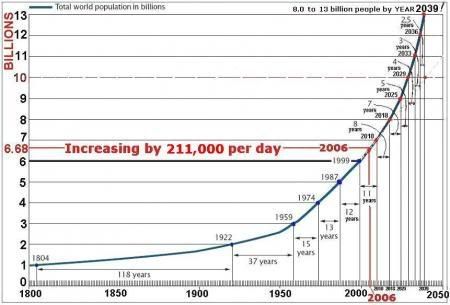

In this cartoon, Watterson uses Calvin's innocence as a young child as his scary costume. By juxtaposing the innocent young boy against the reality of his actual standing in the world, it is obvious to see Calvin's costume is much scarier than what the reader would originally think, which is also why this cartoon is able to make a point. If instead of the cynical cartoon, the reader instead simply saw a model of population trend like the one below, the point would not be the same.

In this cartoon, Watterson uses Calvin's innocence as a young child as his scary costume. By juxtaposing the innocent young boy against the reality of his actual standing in the world, it is obvious to see Calvin's costume is much scarier than what the reader would originally think, which is also why this cartoon is able to make a point. If instead of the cynical cartoon, the reader instead simply saw a model of population trend like the one below, the point would not be the same.

Sure this graph proves the same point of where global population is heading and that any one child is "just another resource-consuming kid in an overpopulated planet." At the same time, the graph fails to have the medium of voice that a cartoon has that can "speak" to the reader and help them und

erstand through means of persuasion rather than simply presented facts. This is the same reason that activist's like Al Gore chose the medium of film production to get points across instead of only writing a book or publishing graphs and statistics in a newspaper. By being able to voice an opinion, either through creative writing or voice itself, a person has a much better chance of getting general people to understand the idea they are setting forth.

erstand through means of persuasion rather than simply presented facts. This is the same reason that activist's like Al Gore chose the medium of film production to get points across instead of only writing a book or publishing graphs and statistics in a newspaper. By being able to voice an opinion, either through creative writing or voice itself, a person has a much better chance of getting general people to understand the idea they are setting forth.All this brings us back to Bill Watterson and why he would create this cartoon in the first place, of which there are many reasons. First off, Watterson was born in Washington D.C., but moved to Chagrin Falls, Ohio at an early age where his mother became a town council representative leaving Watterson with a childhood full of political upbringing. Watterson then moved on to college where he defied his parents wishes for him to go into writing, and instead graduated with a degree in political science. So although this comic could have easily been created by anyone adapt to watching the news and realizing overpopulation is an issue, a person like Watterson with deep political influence is only creating on the topic he knows best.

Calvin and Hobbs was written over a 10 year period mostly during the 1980s. Watterson's cartoons often conveyed a deep meaning but at the same time were generally funny for children to read as well, although they most likely did not understand the true points of the writing. When Calvin and Hobbs first came out an eight or nine year old would see a tiger and a

boy and they would say something that seemed funny, so they would keep reading the strip. Now think as that child matured into a teen and possibly even a college student, the meanings would go from the simple surface judgments to fully developed in depth thinking. The young adult would start to ask questions and be truly persuaded by the writing. Much of this is due in part to the medium used of cartoon writing. As Americans generally go, Sunday Morning Cartoons are as part of our culture as 60s muscle cars and chasing the ice cream truck down the street. That means people respect cartoon writing as more than just a piece of entertainment, but a near priority. If someone puts something like comic reading so high, they must also have the sense to respect what it is saying, and after a time, the points will actually start being driven into their mindset. This is why Watterson stuck with cartoon writing as his means for persuading his points.

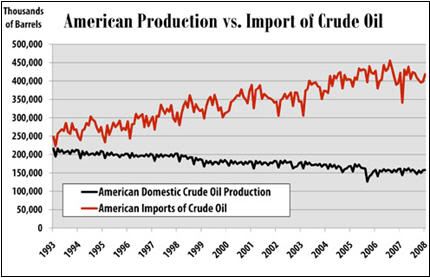

boy and they would say something that seemed funny, so they would keep reading the strip. Now think as that child matured into a teen and possibly even a college student, the meanings would go from the simple surface judgments to fully developed in depth thinking. The young adult would start to ask questions and be truly persuaded by the writing. Much of this is due in part to the medium used of cartoon writing. As Americans generally go, Sunday Morning Cartoons are as part of our culture as 60s muscle cars and chasing the ice cream truck down the street. That means people respect cartoon writing as more than just a piece of entertainment, but a near priority. If someone puts something like comic reading so high, they must also have the sense to respect what it is saying, and after a time, the points will actually start being driven into their mindset. This is why Watterson stuck with cartoon writing as his means for persuading his points.Going back to the cartoon, conventions are a main aspect of why it comes together so well, mostly because the cartoon doesn't stray far from normal cartoon format. There are some key points, for instance, the second panel is obviously where all the action of the cartoon happens, and that should be able to be seen without even reading the text. Watterson uses techniques such as zooming in on Calvin in particular, leaving out a frame and thought bubble in the second panel and also just the simple large amount of text that show this spot as the most obvious source of action in the cartoon. The second panel also yields a bit of political symbolism involving Calvin's trick or treating bag. Substitute Calvin for any general American. Now realize that he is telling this generous person that his costume is simply that of a "resource consuming kid," yet still holding out his bag for more. Surely, anyone could make the connection between Calvin in this strip and the United States as a whole. We know we consume, pollute and dispose of the most, yet we always seem to be reaching out and grabbing for more. Just look at the way we rely on other countries for our oil instead of producing our own. Likewise, the conventional change of covering the face of the person

handing out the candy shows that the person giving out the candy or "exporting " to the United States, can be anybody, but by covering the face, Watterson does not have to make an absolute ethnicity choice of the person, or even the gender. By making these only somewhat hazy connection, Watterson again puts his point across without stepping over the lines of the cartoon becoming an all out editorial persuasive political cartoon.

handing out the candy shows that the person giving out the candy or "exporting " to the United States, can be anybody, but by covering the face, Watterson does not have to make an absolute ethnicity choice of the person, or even the gender. By making these only somewhat hazy connection, Watterson again puts his point across without stepping over the lines of the cartoon becoming an all out editorial persuasive political cartoon.Even with all that in the second panel, the third is nearly as interesting. Though the simple, small amount of words and the very minute amount of drawing may detour most from capturing the full extent of the frame, it certainly has a lot to say. Again with the symbolism, after Calvin gets his "resources," before even getting away from the house, begins consuming what he has been given. Doesn't that sound strangely reminiscent of most industry in America? How about the entire idea of fast food? People go to a fast food drive through and begin eating during the ensuing drive to wherever they are going without even thinking about what they are doing. How many times have we seen or can we remember getting a toy when we were young and needing to play with it as soon as possible before even getting back home? Often times, we were bored with the toy after a week anyway and it went unused. Similarly, Calvin appears to have munched all his candy away as quickly as it was given to him.

Calvin's adventure on Halloween is much more than a mildly humorous attempt at generating a costume out of being too lazy to make one. It truly gives a deeper symbolic look into how Americans generally feel and react to what they receive. Watterson's cynically political outlook on a simple childhood tradition is both comical, but a horrible realization at the same time. True, Calvin's intelligence did get him the candy he wanted, but it also perpetuated the poor cycle of immediate gratification. Using a cartoon as such a medium to get this point across was an excellent idea and Watterson should be commended for such a strong ideas and means of getting his ideas out to a general audience.